The children's advocate

Denny Abbott helped desegregate Alabama orphanages and shuttered a "slave camp." Later on, he headed the Adam Walsh Foundation. His memoir, "They Had No Voice: My Fight for Alabama's Forgotten Children," is out now.

Denny Abbott was 19 before he so much as touched a black person.

In his first summer in col lege, he was back home in Montgomery, Ala., working at the meatpacking plant where his father, an Army veteran with no more than a fourth grade education, would work for the rest of his life.

On that morning, he still carried the memory of the day his father came home from work and found the black maid sitting at the dinner table, chatting with Denny's mother.

"He went into a rage," Abbott recalls, a boy's memory Vivid still at 73. "He humiliated that woman for sitting at the same table as a white woman, my mother never gave it a second thought."

His father stormed out of the room after the blowout, leaving Denny and his mother alone in the quiet, their hearts still racing. She sat down their only child to repeat something she had told him his whole life, behind his father's back.

"She always said we should treat everybody with respect. Those things, we couldn't even discuss in front of my father," Abbott remembers. "That was something between us."

That morning at the meatpacking plant, an African-American man had made a delivery and extended his hand to say goodbye.

Abbott can still remember staring down at his hand -- and taking it. The hand shake was a promise that Denny Abbott would be different from his father in all the ways that mattered.

"I remember it so vividly," he said.

Abbott, who now lives in West Palm Beach, was never blind to race, no, quite the contrary. He set out to speak for those without a voice in America and began a sweeping career as a victim's advocate.

He was 29 when he successfully sued the state of Alabama in 1969 to overhaul a draconian segregated juvenile justice system that made modern-day slaves of African—American children, even though it cost him his job. Years later, as a rape counselor and coordinator of victims services for Palm Beach County, he advised the woman who brought rape charges against William Kennedy Smith. And he became the first national director of the Adam Walsh Child Resource Center as it grew into the country's first National Center for Missing and Exploited children.

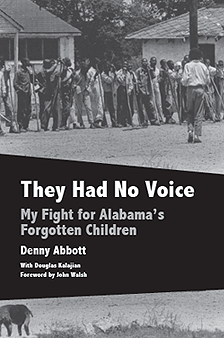

The title of his new book is a reflection of that life-long dedication: "They Had No Voice: My Fight for Alabama's Forgotten Children." (Newsouth, $17.95)

"He's always been a champion for children," said John Walsh, creator of America's Most Wanted, who became a victim's advocate after his son, Adam, was abducted and murdered in Hollywood, in 1981. "I think he knew our pain. our frustration, our hurt and my anger. I have great respect for Denny and the fact that he guided us."

Montgomery was still split down racial lines when Denny Abbott returned from Florida State with a degree in criminology to become Alabama's youngest chief probation of fcer for family and juvenile court.

From his courthouse office window, he could see Martin Luther King Jr. walking out of his church two blocks away to lead a silent march down the main drag. Abbott remembers the freedom riders coming in to Alabama to challenge the segregation laws on buses, and Abbott remembers he regularly rode the same bus route to work as Rosa Parks.

Not only did black people have to sit in the back of the bus: if all the white seats were taken and a white person boarded, the whole first row of blacks had to stand and let that person sit, because blacks could not be in the same row as a white person, Abbott recalls in his book.

Blacks had to pay the driver in front, then get off and go to the rear door to board, so they wouldn't walk by white people.

"Sometimes they'd pay the driver but the bus would pull away before they could get on." Abbott writes. "Other times they barely made it."

All the while, in this crucible, the lessons from his home life rang in his mind: There was his father, using the N-word t with his friends, several of whom proudly admitted they were members of the Ku Klux Klan, Abbott remembers. And there was his mother, sitting , for coffee with the maid, and listening to the lessons she learned from her ownme and church, Baptists and Methodist teaching about justice and equality while his father was out of the room.

But he didn`t have to do more than go to work to see the inequality. As the chief probations officer, he despaired at the substandard detention centers which were Riled primari ly with black children. He brought outside groups to the county detention center so they could see where as many as a dozen children were herded into 10-by-10 rooms for 23 hours a day, deprived of counseling, education or recreation. Most of the children were in detention for being runaways or truant or simply labeled "incorrigible."

"All we did was make delinquents out of nondelinquents," Abbott said. He kept bringing public groups through until the county agreed to consider a bond to build a new youth center, and it passed 8-to-1 thanks to public support, Abbott recalls.

That prepared him for a bigger fight. His work brought him into contact with juvenile offenders detained at a sort-of reform school for black minors of both sexes, called the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children at Mt. Meigs.

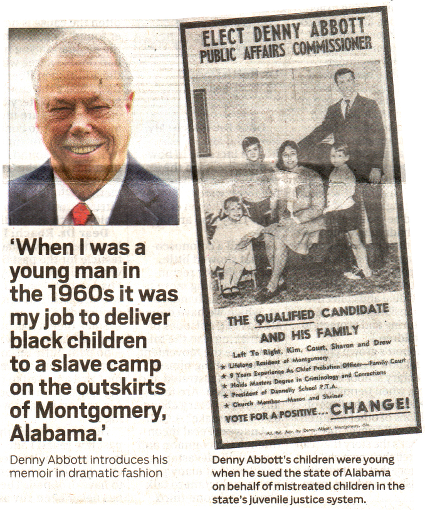

Abbott and his coauthor Douglas Kalajian, a former Palm Beach Post journalist, introduce the memoir in dramatic fashion: "When I was a young man in the 1960s it was my job to deliver black children to a slave camp on the outskirts of Montgomery, Alabama."

"l'm talking about a place where children as young as 12 were held by brute force and put to hard labor in the fields," Abbott writes. "They were worked until they dropped and when they dropped they were beaten with sticks. Often they were beaten for no reason at all and sometimes they were forced to have sex with the men who beat them."

The children detained there received no schooling or counseling, no medical treatment unless they were seriously ill. They were badly fed and the faculties were overcrowded and filthy. They were used as forced labor on farms belonging to members of the Board of Trustees of the facility, all of whom were white. They were regularly beaten with mop handles and fan belts. The director of the facility was a former farmer with a fourth-grade education and no training in juvenile detention. He did a lot of the beating.

"Welcome to the South of the 1960s," Abbott writes. "ln many ways it was no different from the South of the 1860s."

One day in 1969. five teenage black girls. former detainees at Mt. Meigs, showed up at the probation offices asking to see “the boss."

"The girls took turns describing a nightmarish routine of hard labor, beatings and sexual abuse," Abbott writes. One of the girls had been beaten until she miscarried.

By that point, Abbott had received other accounts of mistreatment at the facility, but had found no support from local or state officials to change conditions there.

I looked at my own kids: they had a home, they were protected, they were loved. And these other kids had none of that," Abbott said, and he still is choked with tears by the memory.

That day he decided to do something about it. Together with a local lawyer, Abbott chose a path he knew would make him reviled at home: he sued the State of Alabama in federal court, the same federal courts that were imposing desegregation on the South and incurring the hatred of many Southerners.

The case alleged that the constitutional rights of children at Mt. Meigs were being violated. Retribution was quick. His own boss, a judge, suspended him from his job, for filing the suit without permission.

At home, neighbors cut off friendships. Others went back in their house when he walked by. Shopkeepers he had known since boyhood turned their backs when he stepped in their stores. His phone rang with death threats.

I took that job to work on behalf of all children, not just white children," Abbott said. "I felt a moral obligation to treat everyone with respect."

The courts agreed. The U.S. Justice Department confirmed the facts Abbott alleged. The state was forced to investigate and the governor. Albert Brewer, admitted that the children had been victims of "cruel punishments." Alabama transformed Mt. Meigs within months. The changes included an end to forced labor, the introduction of school classes with qualified teachers, and vocational training.

Shortly thereafier, the federal judge who oversaw the changes ordered the facility desegregated. "This isn't ancient history. This is our country, in our lifetime, and Denny was right there," said Kalajian, the book's co-author. "He could've turned his back and left. He chose to stay and make a difference."

Three years later, Abbott would go on to file a federal suit challenging segregation in Alabama orphanages. That brought him more death threats and cost him his job. But again, he won the larger battle: The state's orphanages, which were all private, were forced to integrate.

His reputation brought Abbott to Florida, where he oversaw the overhaul of juvenile detention centers for the Florida Department of Children's Services, greatly improving the conditions for children in the system. He would go on to act as a career-long victim's advocate who helped pass background-check laws for Florida teachers and as many as 40 other jobs where adults interacted with children.

He was one of the first people to contact the Walshes after their son was killed, and together, they started the Adam Walsh Child Resource Center. As its director, Abbott and John Walsh went on a yearslong cross-country campaign, fighting for individual states and the federal government to allocate money and resources to help missing and exploited children. Their work led to the federal National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, and interdisciplinary agency that uses federal, state, and local law enforcement to do everything from finding missing children (more than 183,000 found to date) to busting child sex slavery rings.

"If he thinks something is right, he'll take it all the way until he's seen it through," said Adele Abbott, his wife of 23 years, "regardless of the consequences."

Abbott is now retired, but still works on children's issues. His latest cause is trying to get the Florida Legislature to force summer camps to obtain licenses and have all employees undergo criminal background checks. That effort was provoked by a series of articles in The Palm Beach Post exposing that some camp counselors have histories as sex offenders or have been guilty of other crimes. So far the legislature has balked, saying requiring such licensing would be too expensive.

"Children have no power of their own; they don't vote and they don't make campaign contributions," Abbott says. "We all have individual and collective responsibilities for the nurturing and protection of children."

Abbott's grown children were still in elementary school in Alabama when Denny Abbott changed the lives of millions of other children they would never meet.

That's the story they can now tell their own children - a story that started with a handshake and a promise.

FOLLOW US

Facebook